Learning Cases

Case 1: Influenza – Stacey

Case 2: Community-Acquired Pneumonia – Jesse

Case 3: Urinary Tract Infection – Ming

Case 4: Urinary Tract Infection – Mary-Elle

Case 5: Urinary Tract Infection – Tharmala

Case 6: Community-Acquired Pneumonia – Doug

Case 7: C. diff – Margaret

Case 8: Skin Abscess – Cheryl

Case 9: Urinary Tract Infection – Bernadette

Case 10: Bronchiolitis – Christopher

Case 1: Influenza – Stacey

Stacey, a 60-year-old woman, comes into your clinic with muscle aches, fever, and general fatigue, which came on suddenly three days ago. Previously, she had felt well. She is not in distress and her vital signs are normal.

Based on her history and a physical examination, you feel there is a high likelihood she has influenza or another viral, flu-like illness. A rapid test for influenza A is positive, in the clinic. Stacey states that she would like antibiotics in order to feel better.

How would you approach your discussion with the patient?

Case 2: Community-Acquired Pneumonia – Jesse

Jesse, a 5-year-old boy, presents to your office with fever, cough, and tachypnea. These symptoms started 3 days ago. He has been eating well throughout this time and has stable vital signs when the pediatrician examines him.

A rapid test, performed by the clinic nurse, is negative for SARS-CoV2 virus. The chest X-ray results are shown below:

Based on the clinical symptoms and chest X-ray findings, you determine that Jesse is well enough to be treated as an outpatient, but will still require antibiotics to help clear the infection.

Given the circumstances of this case, which antibiotic would you prescribe for Jesse?

- Clindamycin

- Amoxicillin-Clavulanic acid (Amox-Clav)

- Amoxicillin

- Azithromycin

Case 3: Urinary Tract Infection – Ming

Ming is a 78-year-old woman with cognitive impairment and living in a long-term care facility. She is seen by you, her primary care practitioner, after the nurse taking care of her over the weekend called for foul smelling urine. On review, she denies any other symptoms and her nursing team affirms that she is in her usual state of health and her vital signs are normal. A mid-stream urine sample is taken for analysis and is noted to be dark yellow and cloudy. Urine dipstick testing reveals a specific gravity (S.G.) of 1.030, a pH of 6.6, trace protein, a positive leucocyte esterase and nitrite test, and negative results for blood, glucose, and ketones. Over the weekend, the team overseeing her care suspected she might have a UTI, so a urine culture was sent to the microbiology lab. Today, the lab reports a positive test result with >10^8 colony-forming units per L of E. coli, which is significant.

What do you do next?

- Treat with nitrofurantoin for 5 days

- Treat with ciprofloxacin for 3 days

- Treat with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for 5 days

- No treatment necessary

- Repeat the urine culture

Case 4: Urinary Tract Infection – Mary-Elle

Mary-Elle is a 25-year-old woman who comes to see you in your office. She describes a two-day history of dysuria, urgency, and frequency, but denies flank pain. She is afebrile, with no costovertebral angle tenderness. She has had a urinary tract infection previously, the most recent being over a year ago, and recognizes her current symptoms as very typical for her. A urine dipstick urinalysis is done in your office, which reveals a specific gravity (S.G.) of 1.030, a pH of 6.2, no proteins, a positive leucocyte esterase and nitrite test, and a positive result for blood but negative results for glucose and ketones. You suspect that Mary-Elle has a UTI.

What do you do next?

- Treat with nitrofurantoin for 5 days

- Treat with ciprofloxacin for 3 days

- Confirm they have a UTI with a urine culture, and wait for the results before treating

- Send for a urine culture, and treat with ciprofloxacin for 3 days

- No treatment necessary

Case 5: Urinary Tract Infection – Tharmala

Tharmala is a 30-year-old woman who is 11 weeks pregnant and presents for her first prenatal appointment. She is in good general health and denies any symptoms specific to the urinary tract. As part of the general screening, you request a urine culture. The results come back with >10^8 CFU/L of E. coli, which you know is significant. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing for the E. coli shows it to be susceptible to Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, fluoroquinolones, amoxicillin, and cephalexin, but resistant to nitrofurantoin.

What do you do next?

- Treat with Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 5 days

- Treat with ciprofloxacin for 3 days

- Treat with amoxicillin for 5 days

- Treat with nitrofurantoin for 5 days

- No treatment necessary

Case 6: Community-Acquired Pneumonia – Doug

Doug, a 67-year-old man, is brought into the emergency room by his partner who is concerned that he is acting confused and disoriented. Doug can provide minimal history, but his partner, Brad, reports that he has been feeling unwell for the past week, with a productive cough, shortness of breath, and maybe a fever.

Doug has not recently been hospitalized or had any infections. Brad can’t remember the last time Doug had to use antibiotics. They have not traveled recently, and apart from their dog, Ralph, Brad recalls no recent animal exposures.

On exam, Doug has a temperature of 36.9°C, HR 128 bpm, RR 25 bpm, BP 110/70, O2 saturation 89% on room air, with warm and flushed skin. He appears confused, with a decreased level of consciousness (Glasgow Coma Scale of 12/15). On respiratory exam, you hear decreased breath sounds on the right side as well as dullness on percussion over the right lower lobe.

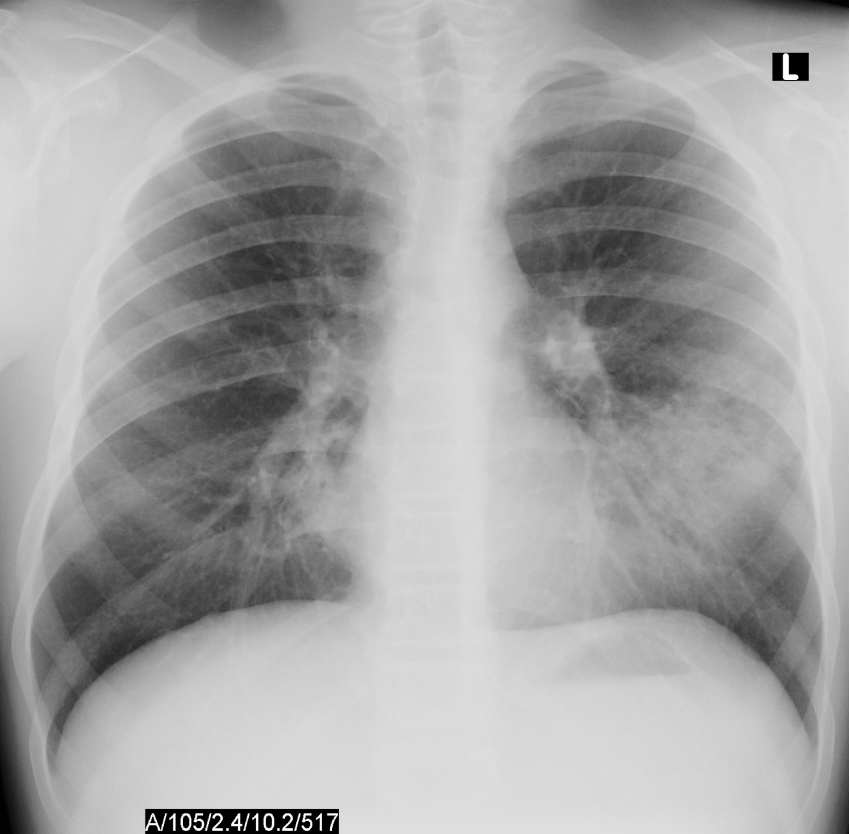

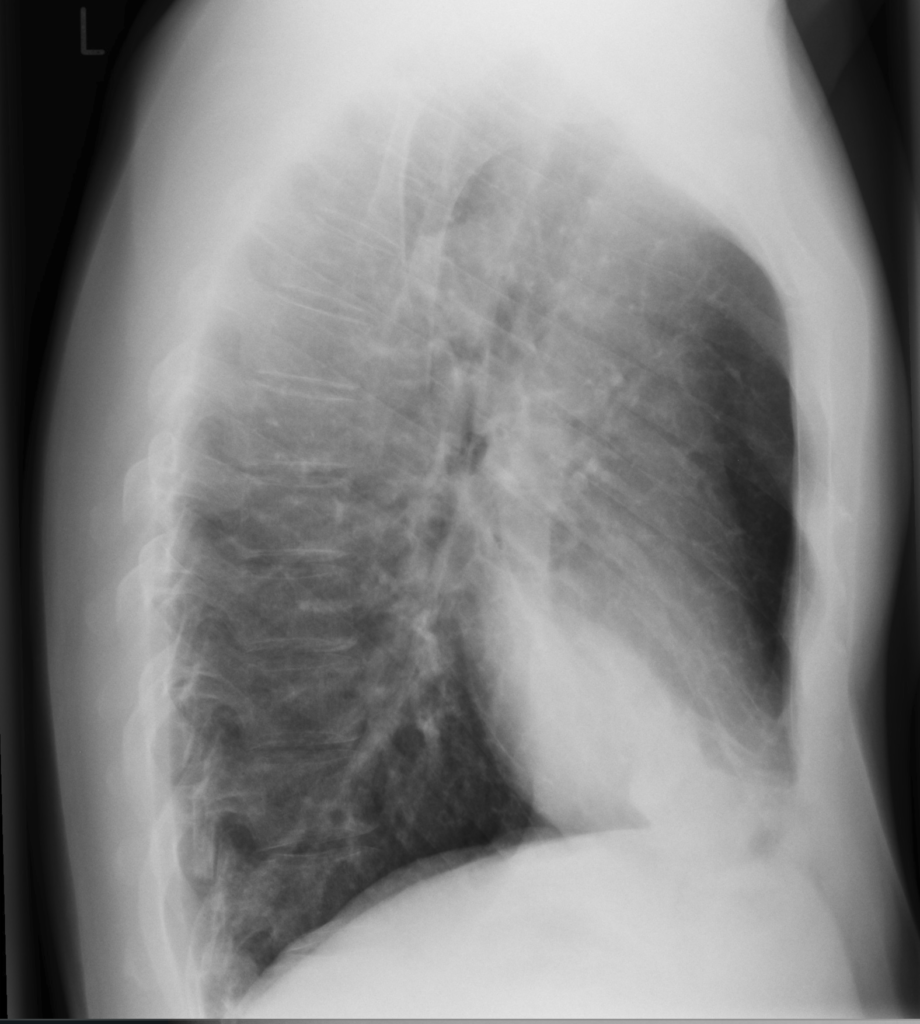

Initial bloodwork shows leukocytosis with a white blood cell count (WBC) of 13.1 x 10^9/L, hemoglobin 160 g/L, platelets 550 x 10^9/L, a lactate level of 4.0mmol/L, a serum creatinine level of 150 umol/L, sodium 140mmol/L, potassium 4.9mmol/L, chloride 98mmol/L. ALT 100U/L, AST 95 U/L, ALP 168U/L. His VBG shows a pH 7.32, PCO2 30mmHg, P02 55mmHg, and a HC03 15mmol/L. Blood cultures are taken from two peripheral sites. You order a chest x-ray, and the results are shown below.

Radiographic images courtesy of Sajoscha A. Sorrentino, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 14979

The x-ray reveals an infiltrate in the right middle and lower lobe, with no effusion of radiographic evidence of heart failure.

Question 1: In addition to community-acquired pneumonia, what is the most appropriate diagnosis?

- Pre-sepsis

- Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

- Sepsis

- Severe sepsis

- Septic shock

Case 7: C. diff – Margaret

Margaret is a 74-year-old patient who underwent a successful left knee replacement surgery and is recovering well. She has a past medical history of: Osteoarthritis, chronic kidney disease, COPD, gout, GERD. She has a recent history of Clostridioides difficile infections, the first of which occurred after a course of levofloxacin prescribed for pneumonia 2 years ago. She was treated with a 10-day course of oral Vancomycin and recovered completely. Unfortunately, she developed a C. difficile infection again, this time in hospital after her recent left knee replacement, once again successfully treated with a 14-day course of Vancomycin.

Margaret is seen in follow-up. She is planning for an elective right knee replacement (the other knee) in the next 3 months. She is worried about recurrence and, as part of perioperative planning, a repeat C. difficile sample was obtained. This revealed a positive result for C. difficile in her stool. She is not currently experiencing diarrhea and reports one bowel movement a day, which is usual for her.

In preparation for her surgery, what would you recommend for treatment of her C. difficile?

- No treatment is necessary.

- Vancomycin 125 mg PO QID for 10 – 14 days

- Vancomycin 125 mg PO QID for 10 – 14 days; followed by a ‘taper and pulse’ extended regimen of vancomycin (e.g., 125 mg PO TID for 7 days, 125 mg PO BID for 7 days, 125 mg PO once daily for 7 days, and then every 3 days for 2 – 3 weeks)

- Fidoxamicin 100 mg PO BID for 10 days

- Metronidazole 500 mg PO TID for 10 – 14 days

Case 8: Skin Abscess – Cheryl

Cheryl, a 46-year-old female, presents to her primary care clinic with a new carbuncle on her upper back that developed over the last 4 days. She tells you that it is quite painful, but does not report any fevers, chills, or night sweats. She has a past medical history of type 2 diabetes and hypertension; a recent culture of a previous foot ulcer 2 months prior was positive for growth of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Her regular medications are metformin, Sitagliptin and ramipril. Upon examination, she looks well otherwise, with a fluctuant, erythematous subcutaneous nodule presenting on the skin above her left scapula which measures approximately 3 cm of induration and erythema in diameter.

Cheryl asks you what would be the next best course of action?

- Incision and drainage (I&D) with a 7-day prescription for TMP/SMX

- A 7-day course of Cephalexin

- A 7-day prescription for Doxycycline and Cephalexin

- I & D, with a prescription for 10 days of Cephalexin and Doxycycline

- I & D, with no antibiotic prescription at this time

Case 9: Urinary Tract Infection – Bernadette

Bernadette is an 80-year-old woman with a history of gastroesophageal reflux syndrome, urinary tract infections, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome rash after exposure to sulfonamides. She presents to Seven Oaks Urgent Care centre with a 1-day duration of fever, chills, nausea, flank pain, urinary urgency, and frequency. She takes pantoprazole regularly, but no other medications.

On examination she does not appear ‘toxic’; she is alert and well oriented. Her weight is 45 kg. She appears slightly dehydrated (decreased skin turgor and dry mucous membranes). Her vital signs show a blood pressure of 135/85 mmHg, a regular pulse of 100 beats per minute, a temperature of 38°C, and a normal respiratory rate and pulse oximetry. Her cardiac and pulmonary examinations are unremarkable. She has no abdominal tenderness or peripheral edema. She has costovertebral angle tenderness to percussion on the right side.

Investigations reveal a white blood cell count of 12.8 cells/uL (with increased polymorphonuclear leukocytes), normal hemoglobin, creatinine, and electrolytes. Her urinalysis reveals 20-50 white blood cells per high-powered field, 2-3 RBCs/hpf, and positive nitrites. You suspect Bernadette has right-sided pyelonephritis. You order blood and urine cultures and initiate intravenous fluids, an anti-emetic, and oral ciprofloxacin. She feels better in 3 hours and is discharged home; the ciprofloxacin prescription is sent to her pharmacy.

The next day, she calls the department and states she is still feeling very unwell. She has had minimal oral intake due to ongoing nausea, and she complains of rigors and feeling lightheaded. You advise her to return to the department. Her vital signs are: blood pressure 105/65 mmHg, pulse 115 beats per minute, temperature 39oC.

The urine culture is not yet available, but the microbiology lab calls to report that the patient has a positive blood culture for Gram-negative bacilli, identified as Escherichia coli.

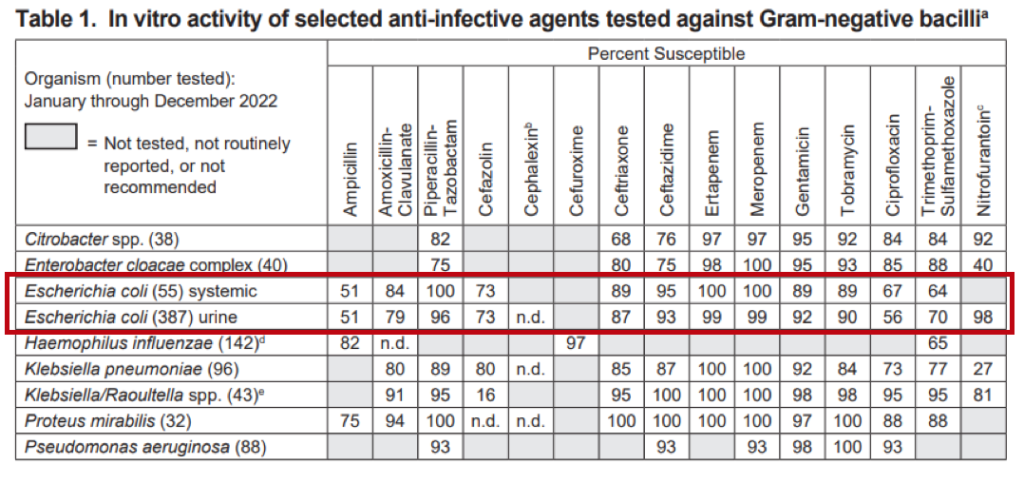

Question: Is ciprofloxacin the best antibiotic for Bernadette? Are there any local resources available to give an idea about the likelihood that her E. coli is resistant?

Case 10: Bronchiolitis – Christopher

Christopher is a 9-month-old girl who was brought into your local emergency room by her parents. She was born at term and has been healthy at her regular well-child visits. She has received all her recommended immunizations, including two-doses of influenza at six and seven months old, and her first Covid-19 immunization. Her parents describe a four-day history of cough and congestion. For the past two days she has had intermittent tactile fevers, and has been fussier. She is breastfed and eats various soft-solid foods. She has been eating less but is breastfeeding well and has been having four to five wet diapers each day. Both her parents and her two-year-old brother have had cough and rhinorrhea.

At triage, her vital signs are as follows: temperature is 38.5° Celsius, heart rate is 160 beats/min, respiratory rate is 50 breaths/min, oxygen saturation 94% on room air, and blood pressure is 93/58. She has been given a dose of acetaminophen prior to your assessment. On examination, you observe a settled infant with mildly increased work of breathing. There is slight subcostal indrawing, but no intercostal indrawing or nasal flaring. On auscultation, there are coarse crackles and scattered wheezes bilaterally. The remainder of her examination is unremarkable.

Question:

You suspect a diagnosis of bronchiolitis. What is the most appropriate next step?

- Order a chest x-ray to evaluate for pneumonia

- Provide nasal suction as needed and observe oral feeding in the emergency department

- Prescribe amoxicillin for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia

- Order a nasopharyngeal swab for QUADRUPLEX NAAT to evaluate for Influenza, RSV, and Covid-19

- Initiate continuous pulse oximetry and observe in the emergency department